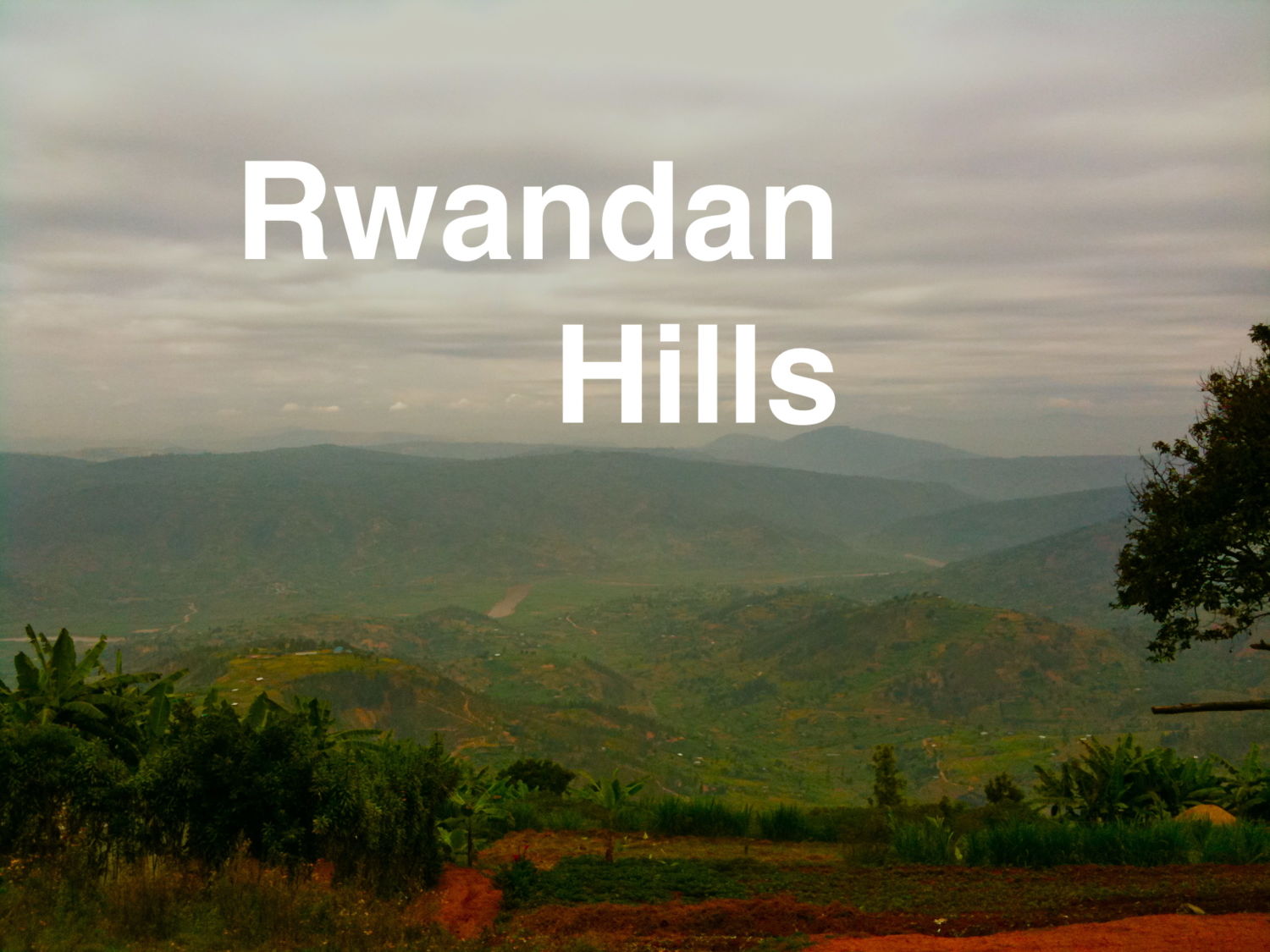

Rwanda is green and clean, a marked difference from yesterday’s Kenyan diesel and red dust. Here you are either walking up or down, as the nation is made up of a collection of hills, tall, but not quite mountainous.

When you say Rwanda, most peoples first thoughts are of the genocide. I remember listening to the stories of General Dallaire’s and his memories of those horrific 100 days. I suppose this is why my first stop today was the genocide museum.

Situated on the side of a hill (like all buildings in Rwanda), the museum walked me through the division created between Hutu’s and Tutsi’s. Impossible to see to outsiders, these two tribes, formally known for their integration, were actively influenced by foreign governments to highlight their differences.

What made them different? Mainly, the measurements of noses, and quantities of cattle.

Racist policy met, divisions in place, and the minority Tutsi were elevated while the remaining 82% Hutu and 1%Twa were relegated to secondary citizenship. A recipe for conflict was actively pursued.

Predictably the majority revolted. Horrifically the lessons of discrimination, so institutionalized, were hard to shake. The oppressed became the oppressor. Leaders on the radio dehumanizing the Tutsi with calls for the cockroaches to be exterminated. Militias were trained, Machetes were distributed, NGOs and churches cried out shrill warnings. The killers took their time, they practiced on smaller groups. Killing a few dozen here, a hundred or so there. Eventually you get good at what you practice, you don’t even need to think about it anymore.

The world yawned in horror.

The new 10 commandments of the Hutu were developed and promoted in 1990. 1. No Hutu should marry a Tutsi, then nine more of the same. This document seems strange to me, it wasn’t written very long ago. This was not the historical sepia toned tape of the Nazis – this happened as I began college.

I paused to watch the video. Images of men, women and so, so many children brutalized and burnt. The trace of a bullet across a child’s face leaves a line in the flesh. The grainy swarming and hacking death of men by their neighbors who carried the machetes.

Yesterday, they had fed one another’s children, today they cut off their fingers.

After walking past the images, we heard the voices of survivors, wondering why they survived? Why they are still here? Guilty somehow, as only a victim can comprehend.

The footage of the Gacaca, the traditional community court, is so chilling in its simplicity. No one hides behind legal words. A man in a pink shirt stands and faces the community. He recounts his story, of who and where he cut his neighbors daughters with his knife, he tells the names and is asked to slow down, to repeat the names, so the official record-keeper can write everything down. He speaks so matter-of-factly, listing the others who were with him, the people he collected for slaughter, how and what they did. The community listens quietly, as an outsider it seems impassive. I actively try to reason why? Has the horror been so common, too common? Perhaps the silence is the silence of confusion? Or maybe the best response to madness?

Maybe they know there is no rational reason. Is evil rational?

The walls of photographs are full, tightly packed over four large walls, and yet it only carries the faces of 2000. Where are the images of the other 998 000? Is there anyone left to hold their picture and wonder as I do? The images are common-place, these are not bureaucratic mugshots, nor are they the efficient record of a deathsquad recording the victims. These photos are plucked from the albums of everyday life. Young men standing outside a shop, a crate of bottles in the foreground. A woman, obviously cropped from her wedding photo, the dislocated arm of her husband encircling her waist. People smiling, posed and unposed, unaware that they are destined for a memorial wall of murder.

I pass through the children’ memorial garden and read their bewildered questions, we head towards the car, and as I am about to walk away, a final small wooden sculpture is revealed, the simple caption, “I did not make myself an orphan”

Why do you think we say ‘never again’ so often?

Mark Crocker